Inflation management poses newer challenges

C. R. L. NARASIMHAN

The Hindu

April 4, 2011

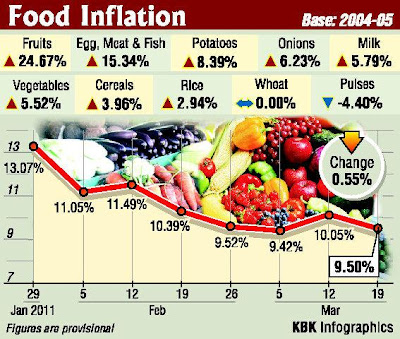

The surge in food inflation, which crossed double digits on March 12 after retreating over the three previous weeks, appears to have caught the government by surprise. However, even when the weekly Wholesale Price Index-based food index was declining, the prices of milk, eggs, poultry and meat had remained firm. Economists had for quite some time assigned a specific cause for this trend: as incomes rise the food basket of an average family gets diversified.

The average family can afford to move from coarse grains to cereals, milk, eggs, meat and so on. Since this trend will not reverse, the price rise in these ‘protein' segments will remain high well into the medium-term. Adding to the discomfiture of policymakers has been the fact that there is no respite from the high global oil prices. Indian consumers expect domestic fuel prices to go up. This will harden inflation expectations, already at high levels.

Whether it is on account of an unexpected rise in food prices or due to a surge in the prices of non-food manufactured products or a combination of several factors, inflation has always been in the news.

Recently, the Finance Minister said that it would be possible to maintain inflation at ‘reasonable levels.' What those reasonable levels are, whether in fact the price rise is a result of high economic growth are all subject matters of considerable interest.

The Economic Survey 2010-11 looks at inflation from different perspectives. In its second chapter ‘ Micro-foundations of macroeconomic development', the survey observes that the period of high growth accompanied by inflation calls for some nuanced analysis of the impact of inflation.

Since not all sections are partaking of the fruits of growth in the same way, policymakers have to worry about the worse-off and vulnerable sections of the society.

Hypothetically, it is possible that the average Indian is better off as the per capita income growth has been of the order of about 7 per cent annually. However, some poor people are actually worse off because their nominal incomes have hardly grown and inflation has negated that growth. For a country having inclusive growth as a model this is a serious concern.

Rise in food prices

The rise in food prices especially impacts on the poor more severely than on others.

According to official statistics, the bottom quintile of India's rural population spends about 67 per cent of their aggregate household expenditure on food. With food inflation at around 10 per cent during the most part of the year, some in this group would be worse off despite the high real GDP growth. Then that is the reason why the official policies have to be supportive of the poor-through appropriate food security schemes, dependable micro credit, basic health support and so on. Such policies are there to stay.

Despite the best efforts, inflation will be higher than the 3 per cent or so that prevailed earlier.

There is an interesting connection between inclusion and inflation. A number of people especially in the rural areas keep their savings as cash at home.

Financial inclusion

Financial inclusion aims at persuading these people to deposit money in a bank. The previously idle money would then enter the financial system and add to liquidity. Admittedly financial inclusion, a high priority policy objective, really encompasses a number of initiatives — creating the financial infrastructure in previously unbanked areas, financial literacy and so on. That such a laudable objective should stoke inflation has not been widely understood so far.

There is enough evidence from around the world that monetisation of the economy and bringing more and more people into the formal financial system contribute to an overall pressure on prices.

Another generally beneficial development, globalisation or integration of the domestic economy with the global economy, can also push up prices in India.

In poor countries, the purchasing power parity (PPP) is low. This means the kind of living standard one can have in a poor country with $100 is considerably higher than what one can achieve with the same money in the U.S. and other advanced economies.

But by the time a country becomes industrialised, the PPP correction has to become smaller.

This happens partly because of exchange rate alignments but more substantially because the prices of basic non-traded goods and unskilled labour in the formerly poor countries rise and partly catch up with prices in industrialised countries.

Looking at the future, given that the Indian economy is expected to be on a high growth path, inflation will also remain high.

According to the Economic Survey, the country will have an average annual inflation of nearly 5 per cent during the next decade or so. That forecast is arrived after taking into account several likely scenarios, such as a spurt in real per capita incomes and its impact on prices.

All these suggest the need to revisit some of the standard policies for managing inflation. India's growth process has to be inclusive and there must be better designed systems for providing security to the vulnerable.

Source: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/article1596885.ece?homepage=true

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét